One of the risks that investors face when buying shares on the stock market is the potential for a stock bankruptcy.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, businesses in the private sector are constantly collapsing.

The data shows that:

- 20% of companies fail in their first year.

- 30% fail in their second year.

- 50% have gone bankrupt within five years.

- 70% collapse within 10 years.

While publically-traded stocks are typically more established enterprises, they are far from immune to the threat of bankruptcy. In fact, here in the UK, the rate of insolvency has surged by 81% in the last three months versus a year ago. And it’s not just small businesses either.

The world’s second-largest cinema chain Cineworld recently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

But this is where an important question arises. What happens to investors when a stock declares bankruptcy?

What is stock bankruptcy?

Bankruptcy refers to the legal proceedings a person or corporate body initiates when they cannot repay outstanding debts or obligations.

Here in the UK, bankruptcy proceedings are also known as insolvency proceedings. So what, then, is stock bankruptcy?

Stock bankruptcy refers to instances where a publicly listed company can no longer meet its financial obligations and has to cease all operations.

These tragic situations affect many players beyond just the shareholders. Court supervisors, administrators, employees, owners, customers, suppliers, banks, creditors, and even the general public can be adversely affected.

Because creditors and bondholders have the highest priority of repayment, insolvency often results in shareholders being left with next to nothing. But there are some instances when a company survives and eventually thrives after a serious capital restructuring of the balance sheet.

The odds of recovering investments in an insolvent business are slim, to say the least. But it is possible, depending on what type of bankruptcy is happening. Yes, there is more than one.

What are the different types of stock bankruptcy?

Depending on the circumstances, a company can file for Chapter 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, or 15 bankruptcy. Each works slightly differently and has different outcomes for stakeholders. But Chapters 7 and 11 are the most common.

Chapter 7 Bankruptcy

In this scenario, things are pretty much game over for shareholders. The company does not see any path to recovery and decides to cease operations immediately. It then liquidates all its assets and holdings to try and repay as much of its debts as possible.

The order in which stakeholders are paid is:

- Secured Debt Holders (Senior then Junior)

- Unsecured Debt Holders (Senior then Junior)

- Preferred Stockholders

- Common Stockholders

Typically there is almost always nothing left for shareholders once liquidation occurs and the shares fall to zero, leaving investors with nothing.

Chapter 11 Bankruptcy

In this scenario, a corporate body seeks bankruptcy protection of the law from its debtors. The goal here is to reorganise and restructure the group’s underlying fundamentals to try and return to financial strength.

For creditors, this often means having to forgive a chunk of loans. While this isn’t ideal, most creditors are willing to do so as it improves the probability of recovering some of their previously lent capital instead of getting nothing.

During a Chapter 11 bankruptcy, an independent administrator is brought in to oversee operations, help cut costs, liquidate non-core assets, and formulate a plan to return to profitability.

This bankruptcy process doesn’t always work out. And suppose no saving grace can be found. In that case, the administrator switches tactics to find the highest possible liquidation value for the company’s assets and holdings to repay as many outstanding loan obligations as possible. This is what happened with Lehman Brothers in 2008.

But sometimes, a business can be revived. For example, in 2009, General Motors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. At the time, its equity quickly became worthless. But the administrators were able to turn things around. And today, it remains one of the largest car manufacturers in the world with a £60bn market capitalisation.

What can a shareholder do next?

Honestly, not much. A stock bankruptcy is disastrous regardless of its type. And even though Chapter 11 keeps the possibility of a recovery on the table, the process could take years before recovering, even in the best-case scenario.

Shares will likely become worthless if a turnaround strategy fails, leaving investors with nothing. This is why evaluating a firm’s solvency is such a critical part of the stock picking process. And we’ve written a short free guide to help investors do just that.

Final thoughts on stock bankruptcy

Going back to the earlier example of Cineworld, when it filed for Chapter 11, Cineworld shares tanked by more than 60% in one day. This perfectly demonstrates the dire situation that is a stock bankruptcy.

While these can sometimes emerge as a surprise, in many cases, it’s predictable. Researching and analysing a business before committing to any investment is critical for long-term success. In the case of Cineworld, we spotted cracks over a year before bankruptcy entered the headlines.

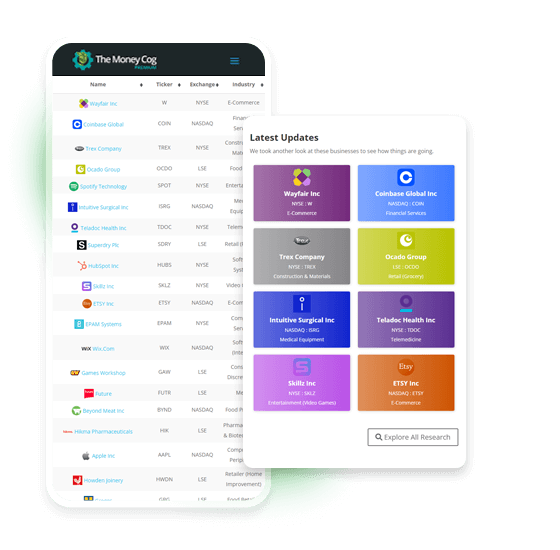

To that end, The Money Cog has two free guides currently available that cover how to perform a quick liquidity and solvency analysis to help steer clear of potentially investing in a future bankrupt company.

Discover market-beating stock ideas today. Join our Premium investing service to get instant access to analyst opinions, in-depth research, our Moonshot Opportunities, and more. Learn More

Prosper Ambaka does not own shares in any of the companies mentioned. The Money Cog has no position in any of the companies mentioned. Views expressed on the companies and assets mentioned in this article are those of the writer and therefore may differ from the opinions of analysts in The Money Cog Premium services.